Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Senator Ben Nelson of Nebraska Retiring

This makes the math for the Democrats to hold the Senate exceedingly difficult. Nebraska is Republican state and there's no clear Democratic candidate other than former Senator Bob Kerrey. While Kerrey was quite popular, he has lived in New York City for the past 11 years--not exactly a plus in the Cornhusker State.

All of this means that the Montana Senate race, already one of the tightest and most important in the country for determining party control of the chamber, just became--that's right--even more important.

Hold on to your hats!

Thursday, December 1, 2011

New Poll in MT Senate Race

Four quick points about the poll:

1. The race has been dead even since the very beginning. There has been hardly any change in the numbers in this new poll.

2. This consistency is NOT surprising. You have two candidates who are well-known and are well-defined. It will be hard to move public opinion with campaign advertising in such an environment. In order to move voters in such a situation, absent either an external event that shakes up the race or a mistake by one of the candidates, lots of money will have to be spent on advertising to have any effect on voter opinion at all.

3. The fact that a significant amount of money has already been spent by outside organizations further underscores the second point. That said, money spent on advertising this past summer was not generally targeted at Montana voters (many of whom were spending their precious warm days outside and away from television), but at the political elite and the donor base. This advertising served to get the base excited and perhaps get them to give money. The organizations that did spend money on advertising were also sending signals to other political organizations about the importance of this race and the effort they plan to expend in the upcoming months on the Montana Senate race. This signaling can cause other organizations to take note and decide that the Montana Senate campaign is worth their time and attention as well.

4. Given that the fundamentals of this race have changed very little thus far, I expect--like most close congressional races--that this campaign will boil down to the enthusiasm of each candidate's base and the ground game. For all the money that is spent on advertising, more important and more significant are the resources and efforts spent on connecting with voters personally and through social media.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

Don't Throw Those Out: The Travesty of Eliminating Political Records

Yes, Governor Romney abided by state law. And yes, Governor Romney did preserve some of those records and sent them on to the state archives. But in the end, posterity and history have lost. The State of Massachusetts should establish clearer and firmer guidelines on the preservation of political records, similar to those established by the United States Senate and the United States House. These materials are absolutely invaluable to the researcher, and essential for government transparency. Issues of privacy can be easily worked out by establishing clear restrictions on particular types of materials and closing such records for an extended period of time.

How can we ever hope to learn from our mistakes and successes if we aren't allowed to study them?

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Legislative Effectiveness: Moving Beyond Bill Sponsorships

This past spring, I tried to answer the knotty question of legislative effectiveness. Both Congressman Rehberg and Senator Tester have spent—and will continue to spend—a considerable amount of time making the case that they are more effective than the other. The question, of course, is critical to answering the question of who best represents Montana in the ways in which they do their Washington work. What is interesting, of course, is both have records as incumbent legislators which only further serves to muddle the picture for the average voter.

My earlier analysis focused purely on bills sponsored by Rehberg and Tester, and what was the “final disposition” of that legislation. I put “final disposition” in quotes because the measure of final disposition I used whether the law as sponsored achieved an up/down vote on the either the Senate or House floor and became law. It is this analysis that became the basis for my recent comments in the Bozeman Chronicle which suggested that neither Senator Tester nor Congressman Rehberg have particularly distinguished legislative records. And, as I pointed out in my initial blog, it is really hard for freshmen legislators in the Senate to establish a long record and the rule of seniority makes it hard for individual House members to stand out from their colleagues.

The problem with that metric and my comments as they were reported, however, is that they provide an incomplete picture of both Senator Tester and Congressman Rehberg’s legislative record. Legislative ideas have lots of ways of wending their way through the process and becoming law. The main thrust of a sponsored bill can get wrapped up into another bill, or the idea in a piece of sponsored legislation can be tacked onto another vehicle through an amendment. Unfortunately, these other vehicles are hard to easily quantify and measure.

In short, looking at bill sponsorships and whether the bill got voted on may not be the best way to determine legislative effectiveness. As a recent press release from the Tester campaign points out, with fewer bills being passed each year, legislative ideas are increasingly emerging in longer omnibus style legislation—particularly in the Senate.

In a press release dated November 7, 2011, the Tester campaign put out a fairly comprehensive list of Senator Tester’s legislative record to date. Note that most of the legislation initiated by Senator Tester became public law by either amendment or being rolled up into other legislative vehicles. According to this press release, then, Senator Tester’s legislative record is much more robust than looking at sponsorship patterns alone. I reproduce the press release from Senator Tester’s campaign below for your review:

Key legislation by Sen. Jon Tester now public law

The following is a partial list of bills and amendments either authored or co-written by Sen. Jon Tester that are now Public Law. Since 2007, Congress has often incorporated smaller legislation into larger bills, thus resulting in fewer “stand alone” bills being signed into law.

VETERANS & HOMELAND SECURITY

The Disabled Veterans Fairness Act of 2007 (S.994): Nearly quadrupled the VA’s mileage reimbursement rate for disabled veterans—the first increase in 30 years. Included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008 (Pubic Law No. 110-161).

Rural Veterans Health Care Improvement Act (S.658): Made numerous improvements to health care benefits for veterans in rural states like Montana. Included in the Caregivers and Veterans Omnibus Health Services Act (S.1963, Public Law No. 111-163).

Project Access Received Closer to Home (ARCH) for Veterans (part of Rural Veterans Health Care Improvement Act): Expands access to VA health care in rural areas. Included in the Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008 (Public Law No. 110-387).

Amendment requiring an investigation and report to Congress on the vulnerabilities of America’s northern border (S.Amdt 3117): Part of the Improving America’s Security Act of 2007 (Public Law No. 110-53).

Project SHAD Veterans Health Care (S.2937): Provides VA care to participants of the military’s Shipboard Hazard and Defense program. Included in the Veterans’ Mental Health and Other Care Improvements Act of 2008 (Public Law No. 110-387).

Veterans’ Compensation Cost-of-Living Adjustment Act of 2011 (S.894): Resulted in a cost-of-living increase in veterans’ benefits. Awaiting enactment.

MONTANA’S OUTDOOR HERITAGE

Delisting Gray Wolves to Restore State Management Act (S.321): Removed Montana’s gray wolves from the Endangered Species Act and returned their management to the State of Montana. Included in the Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act of 2011 (Public Law No. 112-10).

Wolf Livestock Loss Mitigation Act (“Wolf Kill Bill”) (S.2875): Reimburses ranchers whose animals are killed by wolves; improves wolf kill prevention measures. Included in the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 (S.22, Public Law No. 111-11).

Preservation of the Second Amendment in National Parks and National Wildlife Refuges Act (S.816): Allows law-abiding Americans to transport firearms through national parks. Included in the Credit Card Accountability and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009 (Public Law No. 111-24).

Cooperative Watershed Management Act (S.3085): Improves management of clean water resources through collaborative input from local stakeholders. Included in the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 (S.22, Public Law No. 111-11).

ON THE SIDE OF CONSUMERS AND TAXPAYERS

Amendment ending a $25/week bonus in government benefits, resulting in a savings of $6 billion for taxpayers: Part of the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization and Job Creation Act of 2010 (Public Law 111-312).

Universal Default Prohibition Act of 2009 (S.399): Prohibits credit card companies from unfairly changing terms on customers. Included in the Credit Card Accountability and Disclosure (CARD) Act of 2009 (Public Law No. 111-24).

AGRICULTURE

Biofuel Crop Insurance Pilot Program (S.1242): Established a crop insurance program for farmers who grow biofuel crops, such as camelina. Included in the Farm Bill of 2008 (Public Law No. 110-246).

Amendment removing family farmers and small food producers from federal regulations they don’t need and can’t afford: Part of the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (Public Law No. 111-353).

RURAL AMERICA

Amendment requiring Amtrak to examine the feasibility of restoring the North Coast Hiawatha route through southern Montana: Part of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act (Public Law 110-432).

Amendment guaranteeing at least 20 percent public health grants goes to rural communities: Part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Public Law No. 111-148).

INDIAN COUNTRY

Tribal Law and Order Act of 2009 (S.797): Improves law enforcement and prosecution of criminal activity in Indian Country. Public Law No. 111-211.

Crow Tribe Water Rights Settlement Act of 2009 (S.375): Ratified the Crow Tribe’s longstanding water rights settlement. Included in the Claims Resolution Act of 2010 (Public Law No. 111-291).

Finally, Senator Tester just came off an important legislative victory. On Thursday, the day before Veteran's Day, the Senator shepherded the passage of a significant veterans jobs bill, which combined his own veterans' jobs proposals and tax credits recently proposed in the President's American Jobs Act. Tester's VOW to Hire Heroes Act passed 95-0. This is an important accomplishment for the Senator, one for which he is justifiably proud.

In a separate blog, I will discuss Congressman Rehberg's legislative accomplishments that go beyond the bills he's sponsored. The take away message I want my readers to have is that the ways political scientists measure legislative effectiveness--such as looking at sponsorship patterns and whether those sponsored measures move directly to a floor vote--are incomplete metrics and do not tell the whole story of a legislator's effectiveness.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Tester-Rehberg: The Third Quarter Fundraising Numbers

Much of the emphasis will be on how Tester continues to outraise Rehberg. That story line is less important: incumbents typically outraise challengers. There are three key questions that must be asked:

1. Does Rehberg have enough money to carry out his plan?

2. What kind of outside support will both candidates get?

3. What's each campaign's burn rate?

I'll look at that information in an upcoming post. Bottom line: both candidates will be well-funded and will have the resources they need to win. Remember, many of the challengers who toppled incumbents in 2006, 2008, and 2010 did not spend the most money. The critical question is this: is there enough money to make the race competitive?

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Tester-Rehberg: Third Quarter Fundraising

This is further evidence, folks, that the Senate race between these two is likely to break fundraising and spending records here in Montana.

More later when the Congressman's numbers are announced.

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Tripartite Representation: Congressional Representation in Small States, Part I

In preparation for my book on the Montana Senate race, I’ve been doing some reading not only about the American West generally and Montana history specifically, but about representation. The key question driving my interest in the campaign is how two candidates—both of whom represent the same geographic entity—represent

The problem with Fenno is his conceptualization of constituencies began with a study of House members representing one district alone. What happens when the problem becomes one of dual representation—or in the case of small states like Montana—tripartite representation? How do senators and the lone congressman carve up the same geographic, election, and primary constituencies? Do they strive to develop independent representational relationships or do they “ride” on the representational relationships of their colleagues?

Wendy Schiller’s excellent book, Partners and Rivals, provides some answers to this question. According to her research, senators develop their own areas of legislative expertise in developing independent reputations. In particular, Senators from the same party are pushed to differentiate themselves from their senatorial colleague in order to receive attention from the media and develop unique impressions among their constituents. Dr. Schiller looks at an impressive range of data to buttress her findings, looking at the committee assignments pursued by senators, patterns in bill sponsorship and co-sponsorship, and coverage by the local media of Senate delegations.

I’ve decided to put Schiller’s model to work in helping me to better understand the representational dynamics that occur in states where three elected officials represent the same geographic constituency: that is, those states with two senators and only one member of Congress. These states are Alaska, Delaware, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming. Before adding the wrinkle of House members, let’s first look at the Senate delegations in these states. Do we see a similar pattern in these small states that Schiller finds among all senators—that is, do we see senators attempting to develop distinctive and largely independent legislative portfolios? For this analysis, we are going to look only at Senate delegations from the states above between 2007 and the present. Second, in this first cut, we are going to limit ourselves to examining the committee assignments pursued by the senators. If Schiller is right and

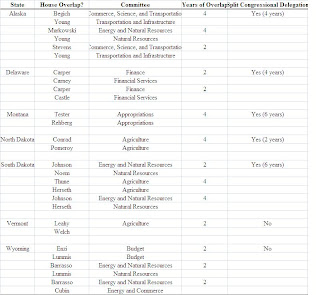

Table 1: Senate Committee Overlap in Small State Senate Delegations, 2007-2011

Given that Senate delegations in small states act very much like Senate delegations in other states, what happens when we add another representative to the mix? Is there this same effort to by the representative to generate a legislative portfolio that’s distinctive from the Senate delegations?

I see two competing hypotheses which could explain the committee assignment decisions of House members where they share the geographic constituency with both senators. First, the Diversity Hypothesis. Even in small and relatively homogenous states there are a diverse range of interests which need to be represented. Members of the House of Representatives, both to represent those issues for the benefit of

Second, the Protection Hypothesis. Small states perceive themselves as particularly vulnerable politically in the chase for federal dollars. Most small states receive more money from the federal government than they pay in federal taxes, but those dollars are always at risk politically from the larger states that lose in this deal. In addition, those federal dollars are especially important in the smaller economies of these states and their loss would get noticed quickly and negatively by constituents. To protect those dollars and the interests of

The Diversity Hypothesis would suggest the House member’s committee assignments will not overlap with the committee assignments of the Senate delegation, and the Protection Hypothesis suggests that the House member’s assignments will overlap to some degree with the Senate delegation in that state. It is important to note that the committee portfolios of senators will always be larger and diverse when compared to House members—both chambers have essentially the same number of committees, but the Senate has fewer members. Senators often serve on six or seven committees, while House members serve on two or three.

Table 2: House and Senate Committee Overlap in Small States, 2007-2011

Table 2 lists the committees in each state where the House member overlaps with the Senate delegation. Although the committees are slightly different in both chambers, it is not too hard to identify jurisdictional matches. The first thing you should notice is that while Senate overlap is rare, House members do seek committee assignments which overlap with those of their Senate delegation. The second thing to note is this overlap is often on authorizing committees and not necessarily on prestige committees. This has to do with two key factors. First, it is incredibly hard to get onto a prestige committee in the House. Second, membership on a prestige committee often requires that the House member give up their memberships on other committees—reducing the opportunities for overlap.

Table 2 cannot definitely answer whether the Protection or Diversity hypothesis provide a better explanation for patterns in House committee assignments and their overlap with Senate delegations. In order to provide some hints a relative measure of overlap is required: how much total overlap might we observe in a congressional delegation and how does this maximum possible overlap compare to the overlap actually observed? Table 3 provides a crude measure of this. The measure is crude because, quite simply, the size of committee portfolios is not a constant. Some senators and representatives have many committee assignments, others have fewer—and the patterns differ from state delegation to state delegation. To deal with this, I calculated three statistics for each congress: the percentage of Total Overlap, the percentage of House Overlap, and the Maximum Possible House Overlap. These are described as follows:

Maximum Possible House Overlap: The number of committee assignments held by the House member multiplied by two divided by the total number of committee assignments of the entire congressional delegation. For example, the Alaska congressional delegation collectively hold 11 committee posts in the 112th Congress.

Total Overlap: This statistic is calculated in a similar manner, but the numerator represents the total number of committee assignments which overlap in the entire congressional delegation. For example, if two senators serve on the same committee and a House member serves on a committee that jurisdictionally matches with one of his Senate colleagues, the numerator would be four (two Senate committee assignments that overlap plus the House member’s committee assignment and the senator’s committee assignment).

House Overlap: Same as above, but the statistic only calculates the committee overlap produced by the House member’s committee assignments. This allows us to quickly evaluate how much of a state’s committee assignment overlap is produced by House, as opposed to Senate, overlap.

Table 3: Measures of Relative Committee Overlap in Small States, 2007-2011

What does Table 3 tell us about representation in small states on committees? First, the data confirm the findings of Tables 1 and 2: committee overlap in small states is largely driven by House members appearing on committees jurisdictionally overlapping with the committees of their Senate colleagues. As Schiller notes, senators do appear to represent the diverse needs of their states and carve out distinctive legislative portfolios. Although there are distinct differences between congressional delegations, the data also seem to provide more support for the Protection Hypothesis than the Diversity Hypothesis concerning the choices made by House members. One third of the time, the Maximum House Overlap and House Overlap statistics are the same value. On only four occasions are the House Overlap values zero, and the rest of the time there is at least some committee overlap between the lone member of the House and her Senate colleagues. This seems to suggest that while the Senate is a place that pushes individual senators even in small and relatively homogenous states to represent a range of interests in their states, House members do not necessarily feel compelled to carve out distinctive reputations or represent other interests that may not be represented by the Senate delegation. One might conclude that the Senate delegation adequately represents the range of interests, but that conclusion is unlikely. Even the smallest states will have interests that go unheard and unheeded in the Senate. More likely, House members in single-member states either hope to “co-op” the legislative accomplishments of the Senate delegation by seeking similar committee portfolios or to demonstrate clout by seeking committee assignments to allow them to receive singular credit for protecting a state’s interests. It might also demonstrate the importance of legislative cooperation necessary for small states to maintain their outsized clout in Washington—a cooperation that is well-understood by representatives and senators representing thinly-populated states that are extra-reliant upon federal dollars.

This post represents my first cut at the question. I welcome feedback, and will continue to explore this issue with additional data in upcoming posts.